by TRA

The History of the Pentacon Six

Reasons Why Development Stopped

However, behind their “Iron Curtain”, Pentacon and Carl Zeiss Jena seemed to be unaware of the importance of style, appearance and marketing in the hated “capitalist west”. In their artificial world, the consumer – or even the professional – bought what was available (usually after a wait of many years!) and knew that it was wise not to complain, at least, not within earshot of Party members.

The economy of East Germany was distorted by the ideological dogma of the communist régime, with employees in every major organisation (including Pentacon and Carl Zeiss Jena) whose task was purely political: the indoctrination of other staff and surveillance of everyone. According to one report in a TV documentary broadcast in November 2009, under the communist dictatorship in East Germany, there were twelve times more state secret police per head of population than Gestapo in the Hitler years of 1933 to 1945. These were the hated and feared “Stasi” or Staatssicherheitsdienst. And there were thirtyfive times more Stasi per head of population than the figures for the KGB in the USSR at the same time.

This alone, was a major economic drain on the economy, not to mention its effect on those innovators who saw better ways of designing of making things, but were hindered in speaking up either by fear or because – as non Party members – they had been denied positions where their voice would be heard and they could implement improvements. (cf Jehmlich (p 203))

Another factor was the impact of government demands that factories engage in production for military and surveillance purposes. This will be obvious with regards to the war years (1939-1945), but was unfortunately another major distorting factor all the way through to November 1989. Jehmlich refers (p 207) to three (post-war!) phases:

1) In 1946 the Soviet occupying powers put “considerable pressure” on Zeiss Ikon AG in Dresden to produce a military camera for aircraft.For years the research efforts of the best staff at Pentacon, Zeiss and “Meyer” were dominated by the demands of these projects, which met government requirements but did not result in any products that could be openly sold on world markets. Whole manufacturing sections of Pentacon, Carl Zeiss Jena and Meyer-Optik were given over to the production of over 6,000 spying and surveillance cameras between 1977 and 1984 alone. As with all research and development, some projects did not result in serial production, but other projects, given mysterious code names, led to the development of infra-red lenses and the coupling of surveillance equipment to TV cameras. Jehmlich comments (p 208) that these developments, many of them requiring excessive amounts of research, development and manufacturing time and resources, took place at a time of dwindling presence and significance in world markets of VEB Carl Zeiss lenses in the field of amateur photography.2) From the beginning of the 1970s the government ministry responsible for the secret police (das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit) required VEB to develop a special camera with various models for spying, counter-intelligence and surveillance.

3) From 1983/84 priority was given in VEB Pentacon Dresden and in VEB Feinoptisches Werk Görlitz (formerly known as Meyer-Optik, Görlitz) to the preparation of military production of lenses licensed by the Soviet Union. This production began after both organisations were absorbed into Carl Zeiss Jena in another major structural reorganisation.

The irony of this situation was that various of these products reached the peak of their development and entered production in mid-1989, but the collapse of the communist system a few months later led to the disappearance of the potential (government surveillance agency!) markets in the Warsaw Pact countries (Jehmlich, p 209).

The requirement to concentrate on these militarily and politically-motivated projects had resulted in the neglect of research and development for civilian photographic equipment. VEB Pentacon’s staff and resources had been directed away from what should have been their real tasks: concentrating on the modernisation of their design, their production processes and the efficient manufacture of cameras and lenses to constantly-increasing international expectations.

In 1981 a staff member at Carl Zeiss Jena told me that it was not possible to make a 40mm wide-angle lens for the Pentacon Six (or any medium format SLR); 50mm was the widest possible because of the space required for the mirror. He was presumably unaware of the 45mm Mir lens made from about 1970 (Princelle, p 223) by Arsenal, Ukraine (in a “brother” communist country!), the 40mm Distagon made from 1967 (Nordin, p 137) for Hasselblads and Rolleis by Carl Zeiss in West Germany or the compact 40mm lens from Norita – or perhaps he was afraid to comment, in the presence of his communist party “minder”.

In response to my enquiries about zoom lenses for the Pentacon Six – or even for the 35mm Prakticas – he likewise replied that this was not possible. This clearly was a case of a company living in a “parallel universe”, unaware of or denying the existence of the “real world”, where these items were already commonplace (for instance, the Schneider-Kreuznach 140-280mm medium format Variogon, and hundreds of different zoom lens designs for 35mm cameras).

It was inevitable that Carl Zeiss Jena

and Pentacon never

got round to designing autofocus lenses and cameras,

built-in motor drives

or other innovations that were appearing in the 1980s in

other parts of the world.

| By at least the 1970s the East

Germans were aware of

the lack of development and improvements in

consumer goods of all sorts

in their country. While I was in East

Germany in 1978, someone told

me a story that was commonly recounted in the

GDR at the time. It

was about the Trabant, the two-cylinder,

two-stroke car that was the only

vehicle that most East Germans could aspire (and

wait years!) to own.

“Each week in Zwickau (where they make the

Trabants),” he said, “the design

team works on improvements for the car.

They produce technical drawings

with great detail. And each Friday

afternoon they throw all the technical

drawings in the bin. The following Monday

they start all over again.”

And indeed, the Trabant was produced without

technical improvements or

any significant changes for 28 years.

A look at the dates and periods of production of the different Trabant car models is interesting: |

|

|

|

|

|

produced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data retrieved from Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trabant on 31.5.2010.

The similarities with the dates of introduction and periods of production of the Praktisix/Pentacon Six are remarkable:

|

|

|

|

produced |

|

|

|

(prototypes in 1956) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(prototypes in 1964) |

|

|

|

the Pentacon Six TL |

|

|

It seems as though between the mid 1950s

and the mid 1960s

there was a decade of tremendous innovation and

development in East Germany.

Then technological development in that country came to a

full stop.

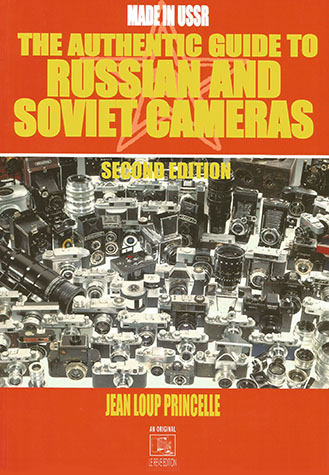

| I have recently (in December

2016) read a section of Princelle’s “The Authentic

Guide to Russian and Soviet cameras” that I had

not previously consulted. The section in

question was written by Valia Ouvrier,

whom Princelle describes as a “professor of

Russian Language”. This is what it says:

“Attentive observation shows us a brilliant apogee

in Soviet photographic creation in the decade

between 1955 and 1965, and a subsequent decline

after 1965.” (p. 29) Ouvrier explores the

possible causes of this sudden decline, including

the costs of the arms race. What is interesting is that Ouvrier has observed the same phenomenon in the USSR that I had observed in East Germany, over the same period of time. |

The second edition of

Princelle’s book

|

To go to the Bibliography, click here.

To go on to the next section, click

below.

36 A half-hearted

attempt at revival

To go to the beginning of the history section, click here.

To go to introduction to the cameras, click here.

To choose other options, click below.

Home

© TRA First published: June 2010,

Revised: January 2017