Using filters with the

Makro-Kilar / Macro-Zoomatar

There is one further detail about the Makro-Kilar /

Macro-Zoomatar that merits description: provision for the

use of filters with these lenses. We saw above that

Kilfitt drew attention to the fact that the

deeply-recessed front element provided what they called “a

permanent lens shade” – the deep front of the lens.

Looking carefully at the front of the older of the two

examples of the lens shown here, the Kilfitt Makro-Kilar,

we note that just below the front edge of the lens there

is a filter thread. This appears to have a diameter

of 60mm, as far as I can see. Although I am not able

to measure the pitch of the thread, I would imagine that

it will be 0.75, which is the most common thread pitch for

filters of this size. However, if we mount

filters here, right at the front of the lens, we will

lose the benefits of the “permanent

lens shade”, and light from outside the image

area will strike the filter from various angles and may

degrade the image. We would then need to find a way

to shade the filter, most probably by adding a suitable

lens shade. But Kilfitt never marketed a lens shade

for this lens, for they had thought of a better solution!

Let us look again at the Kilfitt Makro-Kilar and the

Zoomar Macro-Zoomatar illustrated above.

|

|

[makrok01.jpg]

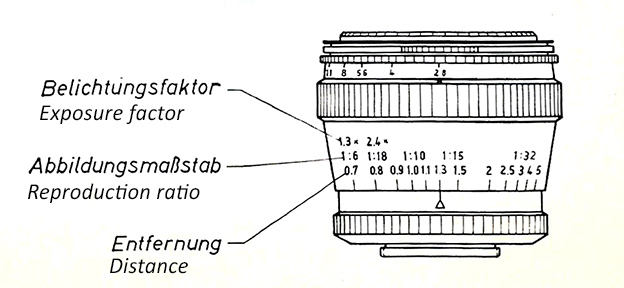

There is a tiny difference of detail at the top of the

lenses, as portrayed in this picture. Can you spot

it?

After looking carefully at the two lenses, scroll down

beyond the gap in the page, in order to see it.

Well, here is the answer:

|

|

|

[makrok01a.jpg]

|

|

The difference? There appears to be a “ridge” at

the top of the newer lens. This “ridge”

has a serrated or milled edge, which can mean only one

thing: it is intended to be removed! Unscrewing it,

we find that it was held in place on a 60mm screw thread

near the front of the lens, exactly like the one that we

had noticed on the older Makro-Kilar. When we

withdraw what we have unscrewed, we find that it is

cone-shaped:

|

|

[makrok02.jpg]

|

|

In fact, it screws perfectly

into the older Makro-Kilar, too, and this lens, too, must

originally have been supplied with an equivalent cone

fitted. For some incomprehensible reason best known

to a previous owner, the cone must have been removed and

then lost. Be aware that many Makro-Kilars

and Macro-Zoomatars are sold without this important

cone! What is it for? Let us take

a closer look.

|

[makrok03.jpg] |

I have here placed the cone

face-down on the table. Near its front, at the

bottom of the image on the left, we can just about see the

thread used to screw it into the lens. But the back

of the cone (the top in this picture) is more

interesting. The final 5mm of the back of the cone

has parallel sides. i.e., this section is

not cone-shaped. About 3mm in from the back there is

a narrow ridge all the way round on the inside. This

ridge is designed to have an unmounted glass filter

placed on it. Slits in opposite sides of

the final 3 or 4 mm (at “North-West” and “South-East”

in this image) create prongs that can be gently squeezed,

if necessary, to hold the filter safely. The image

just above this text also clearly shows two of the

prongs. Scalloped out sections on the other two

opposing sides (at “South-West” and

“North-East” in the image on the left) enable the user to

hold the filter between finger and thumb, to push it in or

pull it out.

The 1950s or 1960s advertisement

for Arnz filters that is reproduced on the right

shows a filter held in a metal ring with similar

prongs that can be slightly bent or squeezed –

either to hold the filter glass more firmly, or to

release it – or to hold the filter ring onto the

lens, since at the time some lenses did not have a

thread at the front, and so filter holders had to

be a push-fit onto the outside diameter of the

front of the lens.

The Kilfitt 90mm Makro-Kilar publicity leaflet

shown above also offers as accessories “Filter

in Gummifassung”, which means “Filter(s) in

rubber mount”. This “mount” was presumably a

thin rubber ring, rather like a rubber band,

around the perimeter of the filter, so that it

would fit in this holder cone without moving or

rattling. I have never seen any such filters

advertised on the internet, but, more than 60

years after they were manufactured, it is highly

probable that the rubber has perished, with parts

of it sticking to the edges of the filter, and

both the filter and the rubber mount have probably

been thrown away.

The same Kilfitt brochure states: “A further and

unique advantage: Filter(s) within the lens

body, protected by the permanent lens

shade. The filters are smaller, lighter

weight and more free from reflections.” (my

translation)

|

|

[arnz_c.jpg]

|

|

|

|

|

[makrok04.jpg] |

As can be seen in this image, the inside

diameter of the filter-holder section of the cone appears

to be 40 or 41mm. For the hard-pressed photographer

in the 1950s or 1960s, who had just bought an extremely

expensive lens, buying a 40mm or 41mm filter would have

signified a considerable saving, compared with the cost of

a filter in a 60mm mount. Moreover, at the time,

filters of this size were available for many cameras, and

indeed were often sold unmounted, so the photographer may

already have had a suitable filter that had been purchased

for a previous camera.

A Kilfitt brochure received in June 2019

indicates that the filter size is “41mm (series

VI)”. This brochure bears the code

“Summary P 58”, from which I conclude that it was printed

in 1958.

What filter would have been most popular? At

a time before colour photography was widespread, the use

of a yellow filter was common, to darken the sky and bring

out the contrast of the clouds. This effect could be

increased substantially with an orange filter, while a red

filter would render the sky almost black. (For an

introduction to filters, see here.)

In the 21st century, when much photography is in

colour, a polarizing filter is

probably the most popular. Of course, many people

have a UV filter almost permanently on their lens,

principally to protect the front element of the lens from

damage. However, with a front element so deeply

recessed as is the case with the Makro-Kilar /

Macro-Zoomatar, such protection may be considered seldom

necessary, unless one plans to use the lens in sand

storms!

Our congratulations to Heinz Kilfitt and his team

on their attention to this degree of detail! No

wonder the brand was so highly esteemed!

|

|

(As a “P.S”, we

will mention that with the 40mm version of the Makro-Kilar

/ Macro-Zoomatar, which was designed for use with 35mm (“full

frame”) cameras, the same filter-holding cone system was

used, although the dimensions were of course smaller, with

an unmounted filter glass of diameter 30mm being

required. As with the Medium Format lenses featured

here, many of the 40mm Makro-Kilar / Macro-Zoomatar lenses

appear to have lost their cone at some time in the

past. With the 40mm Macro-Zoomatar D that I have,

the cone does not screw into the front of the lens; it clips

into place.)

|