by TRA

Format, Focal

Length & Focus

What are the advantages of larger-format cameras?

Elsewhere (here), I

have referred to higher image resolution. This

will be obvious, although as digital technology

develops, the gap between the best digital cameras and

medium format film cameras decreases.

| But

perhaps there is a more important answer.

One that cannot be overcome by advances in

technology: the shallower depth of field of lenses that are normally used on medium format cameras. This means a shallower in-focus zone within the image, with subjects that are nearer to the camera or farther away from it being increasingly fuzzy. |

You might say, “Who wants that?

Isn’t it better to have everything in sharp focus?”

The answer is, “Perhaps.” It depends on the type

of photography and the subject matter. For

instance, portrait

photography is one of the areas

where it is often desirable to limit the depth of field,

in order to direct the viewer’s attention to a

particular part of the image, usually the subject’s

eyes.

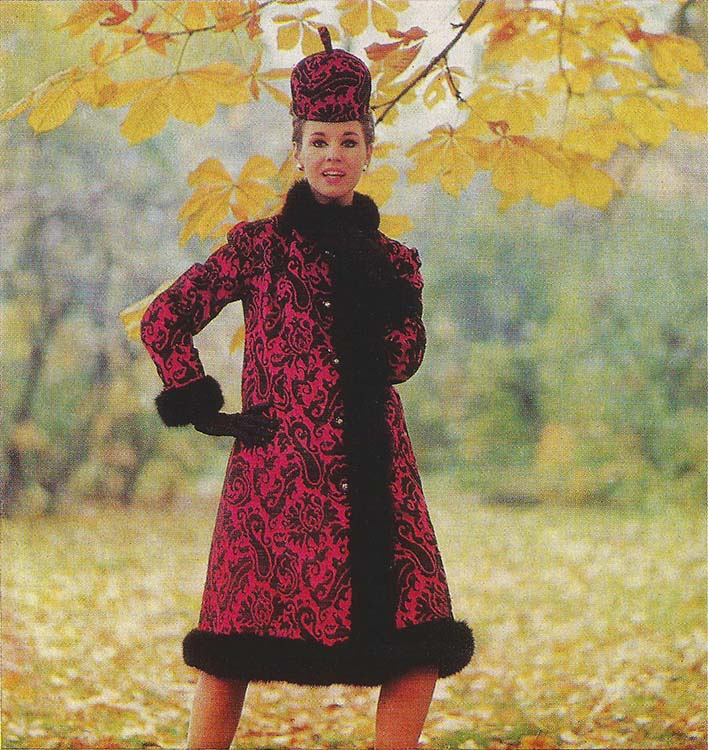

This outdoor portrait, apparently for fashion advertising, would be spoilt if the background were in sharp focus. In “PENTACON six” Camera advertising brochure published by VEB Pentacon Dresden in 1967, p. 7 (Subject and photographer not named) |

|

This image has been slightly cropped to give a vertical picture, as is suitable for many portraits. A sharp background would detract greatly from the impact of the picture. “Schauspielerin Heidemarie Wenzel” by Manfred Uhlenhut (Actress Heidemarie Wenzel) in “Pentaconsix Praxis” by W Gerhard Heyde, 1st edition, 1974, p. 95 |

| Unfortunately,

technical details of lenses and apertures used are

not given. I would suspect that the 80mm Biometar was used for the image on the left and the 120mm Biometar or the 180mm Sonnar for the image on the right, probably at or very near maximum aperture (f/2.8), regardless which lens was used. |

||

Of course, many people just want sharp

photos. They want everything

in the photo to be sharp.

But if we look at professionally-taken portraits, for

instance, we are likely to see that the background is

deliberately out of focus. In fact, on the

TV and in the cinema we may observe scenes of all sorts

where the focus moves backwards or forwards from one

thing that is in the frame to another – without changing

the composition.

To give a different example, if you see in a street a

tree with beautiful blossom on it, you may wish to take

a picture of it. But the picture would

probably be better if the building behind the tree

were more or less out of focus.

Depth of field

|

The zone of sharp focus is

usually called “depth of field”.

It doesn’t change with the size

of the film or the sensor. (However, as

the images from smaller film and sensor sizes

are frequently enlarged more for viewing than

the images from larger film/sensor sizes, it

can appear that the depth of field has

changed. In reality, all that has

happened is that any out-of-focus areas of the

image become more obvious if they are enlarged

more.)

Therefore, if the photographer

wishes to control the areas that are in focus

in his/her images,

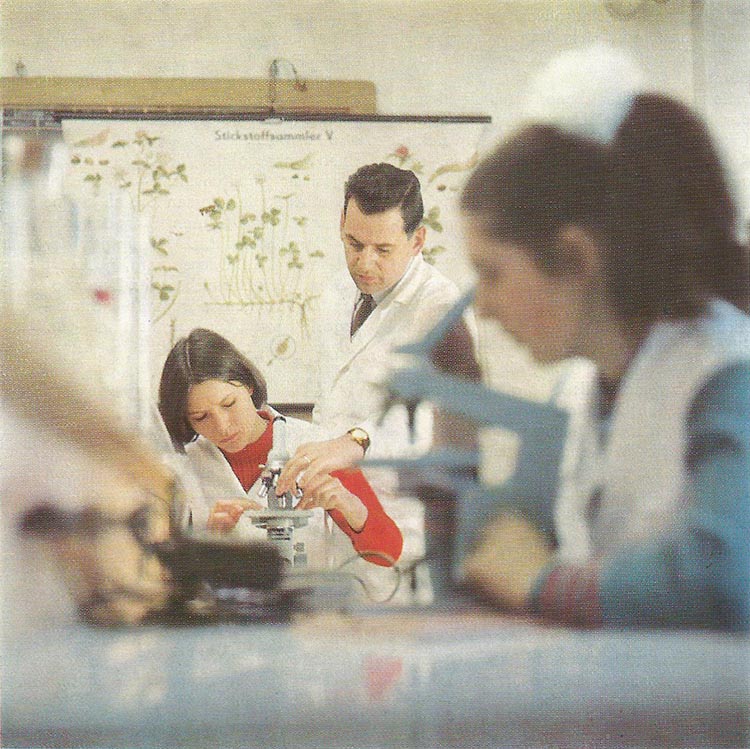

In the image to the right, the very shallow zone of sharp focus has been carefully targeted on the subject, which is framed by out-of-focus components in front of it. The out-of-focus components are sufficiently recongnisable to give a context, while directing the viewer’s attention to the main subject, the young lady working with the microscope and her colleague or teacher. The out-of-focus components thus contribute to the image, instead of confusing the viewer as to what the subject is meant to be. |

|

“Biologiestudenten” by Heinz Dargelis (Biology students) in “Pentaconsix Praxis” by W Gerhard Heyde, 1st edition, 1974, p. 133 |

For more examples of the deliberate use

of shallow depth of field, see here.

|

Advice

for viewing these pictures

As people browse the internet more and more on mobile phones, tablets, etc., it is important to point out that on such small screens it will probably be impossible to see the effect that is described here. A minimum recommended image size to appreciate the differential focus would be in the region of 5"×5" (approx 13cm×13cm), which is normally the minimum size of prints produced for images taken with 120 film. To appreciate the effect fully, I recommend viewing these images at 8"×8" (approx 20cm×20cm) or larger. Like all pictures taken with the Pentacon Six, the original negatives can be easily enlarged to sizes in excess of 2ft×2ft (approx 60cm×60cm) without any loss of detail or image quality. Naturally, to produce copies that can be downloaded from the internet within a reasonable period of time, I have had to reduce the resolution of these scans very substantially. |

The photographer can increase

the depth of field by using a smaller aperture on the

lens. But it is, by definition, not possible to reduce

the depth of field by using an aperture that is larger

than the maximum aperture of the lens!

Here are the standard focal lengths that are common for

various formats, plus the focal lengths that are

desirable for portraits with each of them:

|

Format |

Standard focal

length |

A good portrait

focal length |

|

Samsung S4 |

4.2mm (in 35mm: 31.0 mm) |

12-13.5mm (in 35mm: 90-100mm) |

|

110 film (approx 17 ×

13mm) |

24mm |

45-50mm |

|

APS-C format camera |

Approx 32mm |

57-64mm |

|

35mm camera |

50mm |

90-100mm |

|

6 × 6 medium format camera (54 × 54mm) |

80mm |

150-180mm |

|

4 × 5" (approx 127 × 102mm) |

150mm |

300mm |

As well as using lenses of longer focal lengths on cameras of the format for which they were intended, it is in theory also possible to use them on cameras of any smaller format, assuming that the smaller format camera permits the lens to be changed, and subject to the availability of a suitable adapter.

Example

The 110 format was introduced in 1972,

apparently with the aim of producing much smaller

cameras. The Pentax 110 was the only 110-format

camera that accepted interchangeable lenses. Its

standard lens had a focal length of 24mm.

Regardless what camera it is used on, a lens will always

project an image of the same size of whatever is before

it. The angle of view of the lens won’t

change. But – to give an extreme case – if a 150mm

lens, considered a standard focal length on a 5×4"

camera, is used on a 110 film format camera, the area of

view recorded on the film will be nowhere near the total

image projected by the lens. In fact, it will show

an area equivalent to what one would obtain if using a

300mm lens on a 35mm (“full frame”) camera. This

may be great for photographing distant wildlife, but it

will be no good for portrait photography, as you will

need a studio the size of an aircraft hangar in order to

get far enough away from your subject. And then

you will need a loud hailer or a telephone in order to

communicate with him or her!

However, the optical characteristics of the lens will

not have changed.

| Note that with digital

cameras, we must ignore the effect of

“digital zoom”, since this merely takes a

smaller section of the image and digitally

enlarges it to fill the frame. It

cannot change the optical characteristics

of the lens that the camera has. |

How can

we obtain that control over focus?

Depth of field is calculated by lens manufacturers on

the basis of a series of assumptions, including how much

they think that the image is likely to be

enlarged. The key idea is that they measure or

calculate the size of what they call a “circle of

confusion”, which is the size that a point or a dot is

reproduced if it is out of focus. (The more

out-of-focus it is, the larger it will appear to

be.) The in-focus zone of a lens of a given focal

length does not change with the format. However,

as smaller-format images may be enlarged more than

larger-format images, for practical purposes, different

sizes of circles of confusion are considered acceptable

for different formats. Smaller circles of

confusion are considered necessary for the smaller

formats.

Here is a summary of the depth of field for portrait

lenses on various formats, based on a camera-to-subject

distance of 2.5 meters, with the lens focussed at 2.5

metres and using the data calculated by http://www.dofmaster.com/dofjs.html.

Conversions from metric to imperial are rounded and are

taken from http://www.onlineconversion.com/length_common.htm.

|

Format |

Portrait focal

length |

Aperture |

Near limit |

Far limit |

Total depth of

field |

Approx Imperial equivalent |

|

4 × 5" |

300 mm |

f/4 |

2.48 m |

2.52 m |

0.05 m |

2" |

|

6 × 6 cm |

180 mm |

f/2.8 |

2.48 m |

2.52 m |

0.05 m |

2" |

|

35 mm |

90 mm |

f/2.8 |

2.44 m |

2.56 m |

0.13 m |

5" |

|

APS |

50 mm |

f/4 |

2.28 m |

2.77 m |

0.49 m |

19¼" |

|

50 mm |

f/5.6 |

2.2 m |

2.9 m |

0.71 m |

28" |

|

|

(mobile phone) |

12 mm |

f/2.8 |

1.13 m |

Infinity |

Infinite |

Infinite |

|

12 mm |

f/8 |

0.56 m |

Infinity |

Infinite |

Infinite |

|

|

4.3 mm |

f/2.8 |

0.24 m |

Infinity |

Infinite |

Infinite |

In fact, you are not likely to find a

mobile phone with a 12mm lens. It is likely to

have a lens of approximately 4.3 mm.

This shows us that with a portrait lens on a 4 × 5" or 6

× 6 cm camera, focussing at 2.5 metres and using the

lens at maximum aperture, we will have a sharp zone that

is just 2" or 5 cm deep. Of course, we can increase

the depth of that sharp zone by stopping down the lens

to a smaller aperture.

However, on an APS-format camera (which includes many

digital cameras) with a 50mm portrait lens at aperture

f/5.6, the depth the zone of sharp focus will be 28" or

71 cm.

A mobile phone will normally use face-recognition

technology in order to focus on that subject.

However, the area of sharpness when the lens is focussed

on a subject 2.5 m away will extend from 24 cm (about

9½") in front of the phone to infinity. In other

words, everything will be in

focus. For many subjects, we may want that, but

for others, it is undesirable.

With a mobile

phone, how can we reduce the area of sharpness

and control it?

We can’t.

- Not with a mobile phone.

- Not with the simplest digital cameras with their small sensors and lenses that only have a digital (not optical) zoom.

- Hardly at all with the majority of more sophisticated digital cameras with sensors that are more or less the APS size. Even if they have genuine optical zoom lenses. Even if they can accept other lenses.

As can be seen from above, a 50mm lens

operating at f/5.6 has a depth of field of nearly

three-quarters of a meter, nearly 2½ feet. That

is wider than the distance from one shoulder to the

other on the majority of adults. I

can’t see how it is possible with such a lens to limit

the depth of field, if desired, to the person’s eyes,

for instance. You may of course be able to move

the person away from the background, so that the

background is less sharp and more or less out of focus.

Being able to

control depth of field starts

with cameras that have a format of 35mm

(i.e., a film or sensor size of 24 × 36

mm, now commonly called “full frame”),

and even with them it only really

becomes noticeable if you meet three

criteria:

|

So for many people, controlling depth of

field only begins to be viable with medium format film

cameras, and it is surprising to observe from the above

table that on many occasions you can achieve the same

degree of control with a 6 × 6 cm camera to that which

is achievable with the much larger 4 × 5" (or 9 × 12 cm)

cameras. This is because the lenses for these

larger cameras generally have a smaller maximum

aperture.

And of course, as stated higher up, you can increase

the depth of field by using a smaller aperture.

However, if your imaging device has a lens with a very

short focal length and perhaps a not very large

aperture, there is nothing you can do to reduce

the depth of field.

For more on this subject, see the pages on this website

on

| In April 2017, I have now added examples of depth of field with the 80mm Biometar lens in macro photography. See them here. |

To choose other options, click below.

Home

© TRA First published: August 2016

Revised: November 2017