What about the 30mm Distagon, Zodiak and Arsat lenses?

With these lenses, most straight lines in the original subject are not reproduced on the film as straight lines. For this reason, the 30mm Carl Zeiss Distagon for the Hasselblad is excluded, as it is a “Fish-Eye” lens that renderes straight lines that do not go through the centre of the image as curved or bowed. So are the equivalent lenses in Pentacon Six mount, the excellent 30mm Arsenal Zodiak and the equivalent MC ARSAT. More information on these lenses can be seen, starting here. For examples of the distortion, see here. For certain subjects, these lenses are superb, and one does occasionally see images produced with a fish-eye lens in printed news media. It can be ideal for interior shots where there is no other way of including a large amount of the subject. But fish-eye lenses are not designed for everyday general photography and not for exterior architectural shots.

What about the 38mm Biogon?

There is another alternative: the superb 38mm Carl Zeiss Biogon, which is just a little wider than the 40mm lens. But this lens does not have a retrofocus design. In retrofocus lenses, the space between the back of the lens and the film (or sensor) plane is greater than the focal length, which allows space for the mirror that is required in SLR cameras. “SLR” means “Single Lens Reflex”, and the rationale behind that name is explained here. However, the choice of this name is not obvious for cameras that can take many different lenses, and in fact the German name is more revealing: “Spiegelreflex”, which means “Mirror reflex”.

| The non-retrofocus

design of the 38mm Biogon means that its focal

point is just 38mm from the film plane, and in

fact the rear element is just a few millimetres

from the film plane. By contrast, the

Pentacon Six requires 74.1mm from the rear flange

of the lens to the film plane, and Hasselblad

film-based cameras require more than this,

reportedly 82.1mm for the Hasselblad 1600F and

1000F and somewhat less for the Hasselblad 500C

(sources differ as to the exact distance), but

still greater than in the Pentacon Six. The result was that the 38mm Biogon had to be permanently mounted in a special, ultra slim body in which there was no space for a mirror. The camera was first called the Hasselblad Super Wide, then the SWC and after that the SWC/M. In the image to the right I have greyed-out the film back that had to be mounted onto the camera body.

|

[38Dist1.jpg]  The 40mm Noritar, which took 77mm filters. [N40_01.jpg] |

| However, all of this is somewhat

“academic”, as modifying either of these lenses

to fit the Pentacon Six is likely to be

extremely difficult and perhaps impossible. This is why the announcement in the mid 1980s of a 40mm lens from Joseph Schneider of Bad Kreuznach for the Exakta 66 was so important. It is why I was so keen to buy the lens. However, as far as we can see, few if any of these lenses were completed, and the only one of which I am aware is the one that I bought, unfinished, and got finished myself, as told on this website, starting here. However, it might, in theory, be possible to modify a 40mm lens from another Medium Format camera system. In theory ... |

The

Zenza Bronica 40mm Zenzanon-S lens

A major challenger in the Medium Format

SLR market was the Zenza Bronica company of Japan, who

produced a series of high-quality cameras in 6 × 7, 6 ×

6 and 6 × 4.5 format over a period of more than 40

years, starting in 1959. Lenses for their cameras

were originally supplied by the Japan Optical Industries

Co. Ltd. (Nikon Corporation), with other lenses from

Carl Zeiss Jena, Schneider-Kreuznach and Norita,

according to the Wikipedia

article (consulted on 1.1.19), and in later years

Bronica manufactured lenses itself.

Bronica’s 6 × 6 cameras in later years (apparently 1980-2003) were known as the “SQ” series. A 40mm lens was in the line-up. As far as I understand it (and I am not a Bronica expert), these cameras did not have a focal plane shutter. Instead, each lens had its own, built-in leaf shutter (known as Zentralverschluss in German). These shutters were made by Seiko. Now, having a lens with a leaf shutter is not a problem for a camera with its own focal plane shutter, provided there is some easy way of keeping the leaf shutter open.

An extremely skilled camera technician in Holland, Jaap de Zee, took a 40mm Zenzanon-S lens and modified it for use on the Pentacon Six. He totally removed the Seiko shutter and – much more importantly! – built a mount that maintained fully-automatic aperture control by the lever in the Pentacon Six throat! He also maintained the operation of the aperture stop-down lever on the lens, essential for checking depth of field and for stop-down metering (my preferred method).

I do not generally report on one-off modifications of lenses, but one of the big advantages of cameras with focal plane shutters is the ease with which older and larger-format lenses can be used with the camera. To modify a recent, medium format lens is definitely not easy, because of the limited space available. This skilled technician has, however, succeeded superbly.

Two 40mm lenses for the Pentacon Six: on the left the Curtagon from Schneider-Kreuznach, on the right the Zenzanon-S from Zenza Bronica (modified!) We note on the Bronica lens the red dot to indicate the correct alignment when mounting the lens on a Bronica camera. This is not in the correct position for the Pentacon Six, but the registration pin on the mount is easy to see, and it is right in line with the focussing index on the lens, so the red dot can easily be ignored. [40mm_C_&_Z_02.jpg] |

A slightly higher view of the same two lenses We can just about read the name of the shutter manufacturer, “SEIKO”, low down on the Bronica lens. [40mm_C_&_Z_01.jpg] |

We note that both of these lenses have a maximum aperture of f/4 and a minimum aperture of f/22.

Converting a great

lens from one great camera to another

A great lens starts with

detailed optical calculations of the shape of each

glass element and its position in relation to all of

the other elements. These elements then need to

be manufactured extremely accurately and mounted in a

barrel that will hold them securely in exactly the

right positions. But that is not all. For

high quality cameras, a modern lens must incorporate a

focussing mechanism, along with an external focussing

ring, a scale and distances that can be controlled and

read by the user. And it needs an aperture or

diaphragm: an opening the diameter of which can be

varied to control the amount of light entering the

camera and the depth of the in-focus area – again with

an external ring (the aperture ring) that can be

controlled and read by the user. Then a camera

mount is needed.

Jaap de Zee has kindly sent me some pictures that he

took while converting this lens, and I include a few

of them here.

If we occasionally think that the cost of a quality

lens is high, these pictures may give us a glimpse of

the complexity of such a precision item.

The 40mm Zenzanon S, partially disassembled. [z_s_01s.jpg] |

We may be astonished at the number of components that the lens contains (not all of them visible here!). [z_s_02s.jpg] |

|

| These

pictures may also help us to appreciate the great

level of skill required, and the great amount of

time required, to service or modify one of these

lenses – all of which must be reflected in the

price that we pay to the lens technician for his

or her work. |

||

The optical components of a multi-element lens are frequently mounted into separate barrels, one for the front section and one for the rear. Here we see the two sections of the Zenzanon 40mm S lens. [z_s_03s.jpg] |

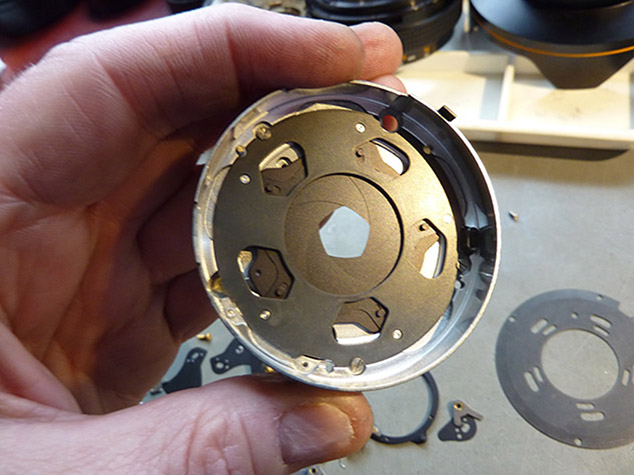

The aperture assembly, seen here, is frequently mounted between the front optical section and the rear one. For lenses with a leaf shutter (including this lens in its original form) the shutter is usually also mounted at this point. [z_s_04s.jpg] |

Jaap tells me that the biggest challenge of the conversion from Bronica mount to Pentacon Six mount was to get the diaphragm working automatically.

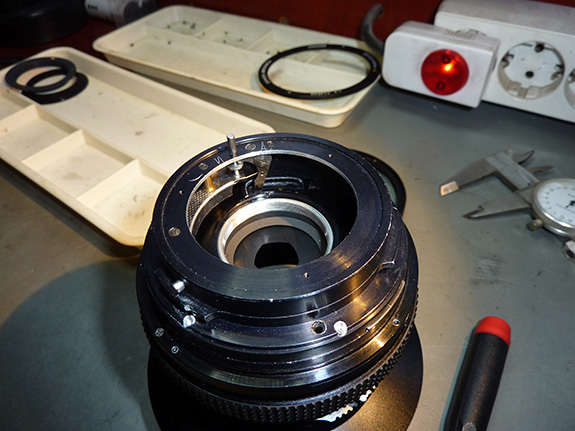

On the top of this ring we can see the aperture pin that must be pressed and released by the camera, to create automatic aperture operation. Underneath it, hidden from view after assembly of the lens, is an “L”-shaped lever that converts the direction of movement from “in-out” to “left-right”. [z_s_05s.jpg] |

Here we see the same ring mounted on the lens, showing us the position of the “L”-shaped lever. Lower down, we can see the aperture blades, partially open. [z_s_06s.jpg] |

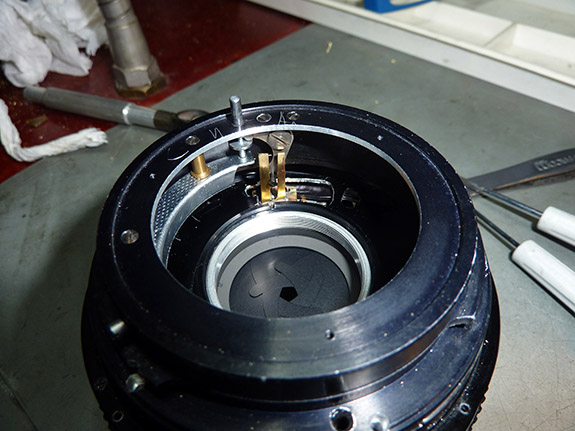

And here we can see the pin at the bottom of the “L”-shaped lever in these three photos (look back to the first picture in this line) engaged with the (bronze-coloured) fork that needs to be moved “left-right” to operate the aperture blades, which are here seen closed down. The fork enables the optical assembly and the aperture blades to move closer to and farther from the camera, as the focus is changed. [z_s_07s.jpg] |

And here is the finished conversion!

The two lenses with their front lens caps: the standard Schneider-Kreuznach plastic cap on the left, and the Zenza Bronica cap, which appears to be made of leather, on the right. [40mm_C_&_Z_03.jpg] |

How should one store and transport such exceptional lenses? Here is one possible solution:

The case on the left was for the first version of the 40mm Zeiss Distagon for the Hasselblad. It is taller than needed for the Curtagon, but the diameter is perfect. The case on the right is reportedly also for the 40mm Distagon, though I suspect that it was for the second version of that lens, which was not as wide. I have had to remove the inner cone, and have provided an alternative soft lining (not visible here), plus some foam padding at the base, as it, too, is taller than needed. [40mm_C_&_Z_04.jpg] |

There is no need for any anxiety about

this; the lenses for Bronica cameras have a high

reputation, earned from their reliable performance in

the hands of professionals over many decades. And

the Dutch technician who modified this lens for use with

cameras that have the Pentacon Six mount did an

excellent job. Infinity focus is spot-on. I

always use the focussing screen for focussing, so I have

not checked the accuracy of the other distance markings

on the lens. However, these have not been changed,

and if infinity is right, they will be right, too.

In September 2018 I posted one picture

from this lens on the page that introduces shift lenses

(here) – in order to

compare angles of view and the effect of using a shift

lens. (This lens is not in a shift mount.)

Here we shall look at some more pictures, all of them

taken with my usual Pentacon Six camera.

First, two images taken with seconds of

each other.

40mm Curtagon Fuji PRO160NS 13/6/18 Leeds Castle, Kent 1/125 f/19 I already posted this image (here) in October 2018, comparing its use with the 45mm Hartblei shift-only lens. [C557_13_C.jpg] |

40mm Zenzanon Fuji PRO160NS 13/6/18 Leeds Castle, Kent 1/125 f/16 (f/19 not available) Note that there are no aperture half-stops with this lens and while stopping half way between two aperture values is not impossible, it is not easy, as the aperture détentes are very closely spaced. [C557_14-15_Z.jpg] |

It is clear that the angle of view is virtually identical with these two lenses. From the markings in the gravel, it looks as though I tilted the tripod head up slightly before the Zenzanon picture, and also there is a tiny bit less of the path on the left and a tiny bit more of right-hand building visible, no doubt also from a slight horizontal movement of the tripod head when changing over the lenses.

There is a tiny amount of vignetting (darkening of the corners) with the Curtagon lens – although you more or less have to be looking for it in order to see it. It could easily be corrected in software, but on this website we like to show things as they really are, before any corrections or improvements. So the Zenzanon looks fractionally better than the Curtagon in this regard.

Let us see two more images shot on the same day at Leeds Castle in Kent.

40mm Curtagon Fuji PRO160NS 13/6/18 Leeds Castle, Kent 1/125 f/16 [C557_10_C.jpg] |

40mm Zenzanon Fuji PRO160NS 13/6/18 Leeds Castle, Kent 1/125 f/16 [C557_9_Z.jpg] |

At a massive degree of enlargement on my large computer monitor, I can see a tiny amount of colour fringeing (chromatic aberrations) in the corners with images from both lenses. However, this is at a level that is not observable at normal degrees of enlargement or from normal viewing distances. It is well within the range that is correctable with minimal tweaks in software, but that is not something that we are here doing. The Zenzanon is sharper in the top right corner than the Curtagon.

| For an approximate

comparison of the angle of view of these 40mm

lenses with the standard 80mm Biometar, here is

the Biometar shot – although I had to walk forward

by about four yards, in order to get the full

height of the building in the reflection in the

water, so the comparison is not totally exact. Exposure details: 80mm Biometar Fuji PRO160NS 13/6/18 Leeds Castle, Kent 1/125 f/16 We will conclude this review of the 40mm Zenza Bronica lens with two panoramic views, cropped from full frame images on my usual Pentacon Six. Both of these are of the village of Aylesford in Kent. Film was again Fuji PRO160NS. As explained here, the resolution of the 6×6 format with excellent lenses is such that the Pentacon Six can easily be used to produce high-resolution panoramic images, merely by cropping the images when printing or using them in electronic format. In fact, although square format can produce some great images (see discussion of this topic here), not every composition is best presented as a square image. When cropping to other formats, if we have composed correctly it is easy to lose any hint of vignetting or lower resolution in the corners of the images that may arise with some lenses.

|

[C557_7_Bm.jpg] |

As is typical for an English summer’s day, even one as lovely as this one, there are some clouds in the sky – even though none of them appear in these two images! – and as they move, so do the shadows that they cast. Thus in the Curtagon panoramic shot, the sun is on the bridge but the leaves in the foreground are in shadow, while in the Zenzanon photo the sun is on the leaves in the foreground and on the church in the distance, but not on the bridge. Nethertheless, we do obtain a reasonable impression of these two lenses, and either of the images is equally acceptable.

For a further test image shot with the 40mm Zenzanon lens, see here.

More images shot with the 40mm Curtagon can be seen here.