Medium Format

Lenses with the Pentacon Six Mount

A comparative test

by TRA

Tilt lenses

And there’s more! – How about

tilting the lens?

Theodor Scheimpflug was (according to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheimpflug_principle)

an Austrian who in 1904 patented an idea describing how to gain

maximum focus when swinging or tilting the lens panel in the

cameras of the time. If you stand facing a flat object, such

as a building, hold the camera with the back exactly parallel to

the building,and focus correctly, the whole building will be in

sharp focus even at maximum aperture (if the lens is good!).

However, in most cases, the picture will not be very

interesting. But if you stand on the pavement (US readers:

sidewalk) looking down the street with the building on your right

side, but you then rotate through 45°, you are likely to get a

more interesting view of the building within its

environment. However, at maximum aperture only a small part

of the building will be sharply in focus, with the bits that are

closer to or father from that point going increasingly out of

focus.

Enter Herr Scheimpflug.

|

|

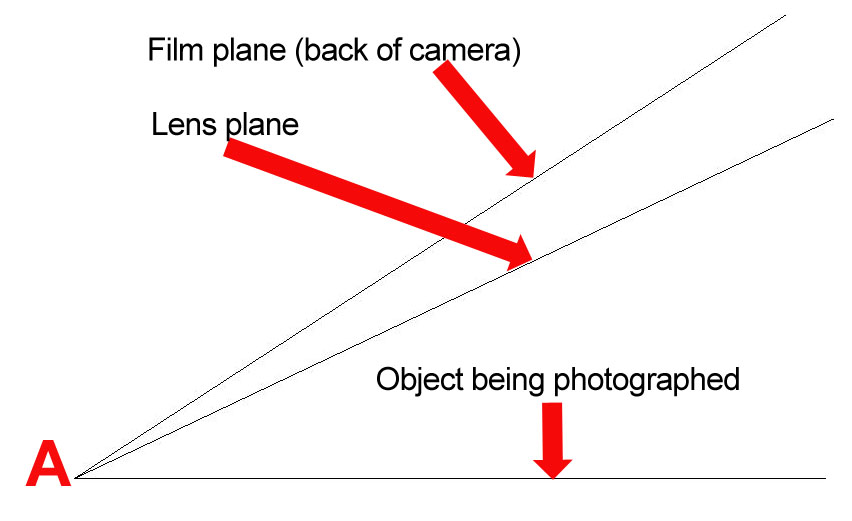

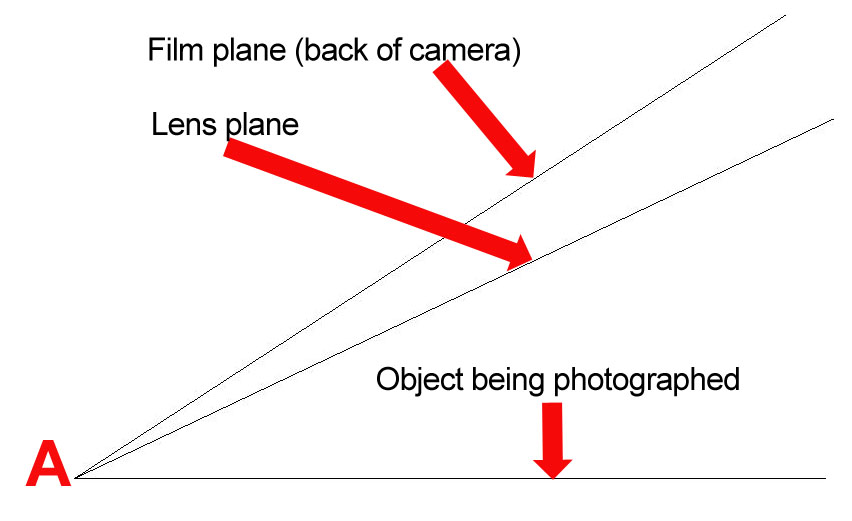

Imagine that this is an aerial view looking down on the

situation that we just described.

The line at the bottom is the front of the building that

you want to photograph.

You are standing holding the camera at the position and

angle shown by the arrow “Film plane (back of

camera)”. If for some reason you need to use a large

aperture, you have no chance of getting most of the

building in focus.

However, if you could swing the lens sideways (rotating it

through its vertical axis), the focus would improve.

Imagine

- a straight line running left and right from the

film back (the top line in this diagram)

- another straight line running through the front

plate of the camera that holds the lens

- a third straight line running along the front of

the building.

If these three imaginary lines meet (point “A”), the image

will be totally sharp across the whole frame.

Thank you, Herr Scheimpflug.

|

However, when he took out his patent over 100 years ago,

achieving this was easy with many cameras: the film (or usually

glass plate) was held at the back of the camera in a wooden back,

the lens was held in a flat wooden plate at the front of the

camera, and between the two there were flexible leather

bellows. Just design a way of swinging the front, and the

focussing problem is solved. Voilŕ, as the French say!

In fact, cameras were designed in which you could swing (from side

to side) tilt (backwards and forwards) and shift (raise, lower, or

move sideways) both the front and rear standards. Moving the

front changes the focus, moving the back changes the shape of the

image, to correct (or even cause!) distortions.

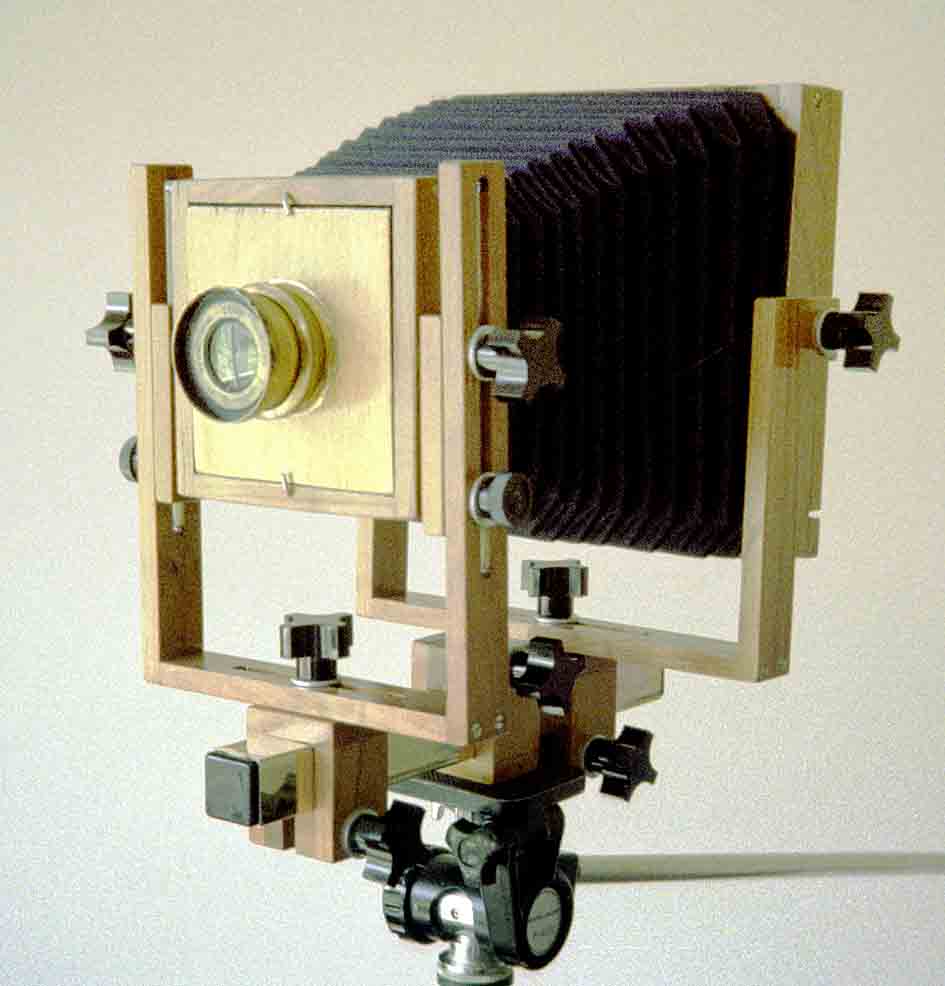

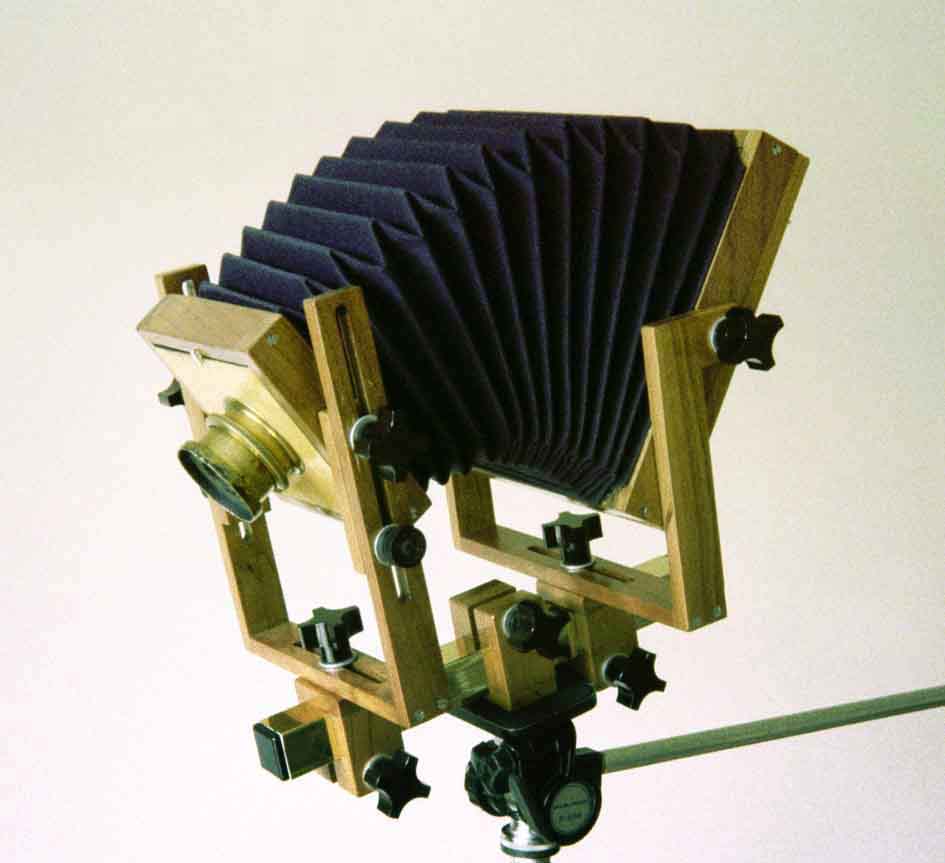

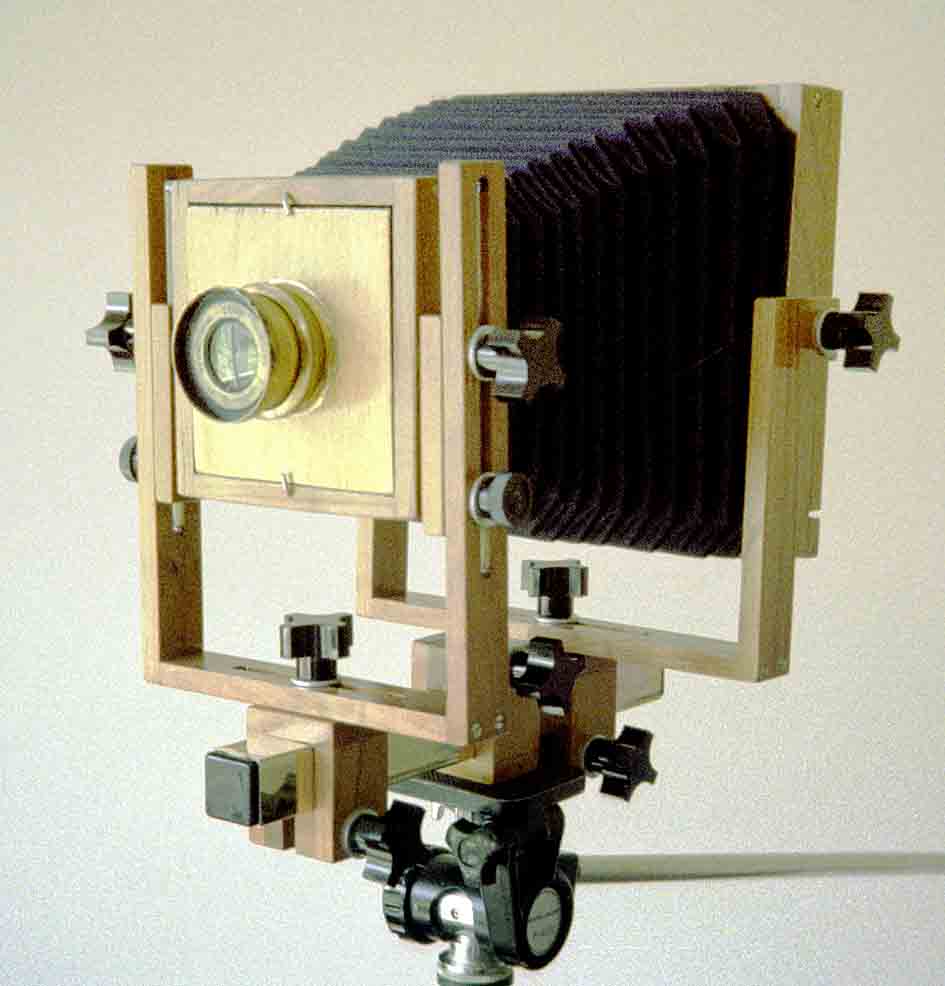

You can still get such camera. I made one, using a kit

manufactured by Bender in the USA.

[C104-29A] My Bender 5 × 4 camera

[C104-29A] My Bender 5 × 4 camera

|

|

The results are superb, but the camera is very large and

awkward to carry and use, and setting up a shot is slow.

Bender’s website is here.

(Note that the camera kit is supplied without

any lenses.)

|

|

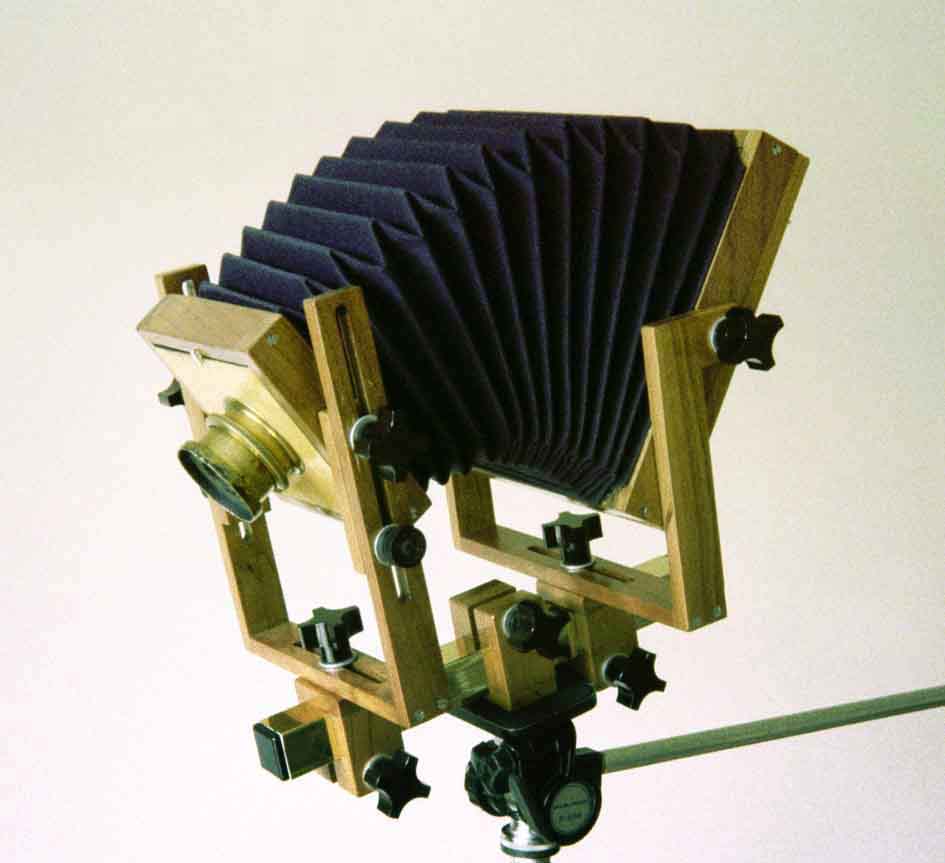

[C104-32A] Both front and rear standards

tilt!

[C104-32A] Both front and rear standards

tilt!

|

So, if you want to use a regular Medium Format SLR film camera,

what do you do?

You can obtain most of the advantages of a “view camera” by using

“technical bellows” on the Pentacon Six. For details,

see here.

Or you can use a tilt-shift lens made by Hartblei!

(possibly still available from Michael Fourman at Kiev Camera)

Hartblei use the 45mm Mir 26 optical components in three

different mounts:

- in the shift only mount described on the previous page.

This enables shift in any direction.

- in a tilt/shift mount with shift in any direction but the

possibility to tilt the lens downwards only

- in a tilt/shift mount with full and independent rotation of

shift and tilt. They call this their TS – PC [Tilt-Shift –

Perspective Control] Super-Rotator. It has two independent

rings that enable the user to rotate either the

direction of shift or the direction of tilt or both!

Use the shift to correct distortion, and the tilt to increase

(or even to reduce!) depth of field.

The Hartblei Super-Rotator 45mm Tilt/Shift lens

And here it is on a Pentacon Six:

fully shifted

fully shifted

|

|

and fully tilted

and fully tilted

|

There appears to be another tilt/shift version of the 45mm Mir

lens, this one produced by Richard Wiese of Hamburg, Germany, with

the name “Technoplan”. You can visit the Wiese-Fototechnik

website here.

[C386-6A: 45mm Super-Rotator, 55mm Arsat shift and 65mm Hartblei

shift lenses

together in one photo, so that their relative sizes can be

compared.]

General requirement

of tilt lenses

Tilt lenses are

most frequently used in product photography, and

when we look at products of any sort (for instance, a meal on a

plate, a toy, a hand tool, etc.) we mostly look down

onto them. It is therefore desirable that any tilt lens

should tilt down.

As stated with regard to shift (only) lenses, it is of course

possible with a square-format camera to use it on its side, or

even conceivably upside-down, although using the Pentacon Six

upside down is difficult, or well-nigh impossible if the camera is

on a tripod -- and most product shots are taken with the camera on

a tripod. (I am of course aware that there are some tripods

that can mount the camera upside-down at the bottom of the centre

column, but this is not particularly convenient for most product

shots.) You can see the set-up for a product shot with a

tilt lens here. (It is in

fact the next page, so you can if you wish finish reading this

page and then click on the link at the bottom of the page to the

test of the Super-Rotator.)

However, a big plus of the Hartblei 45mm Super-Rotator is that it

has two, independent, rotation mechanisms:

- one enables the user to shift the lens in any

direction;

- the other enables the user to tilt the lens in

any direction (regardless of the direction of the shift).

In my opinion, if one is only buying one tilt lens, the

extra flexibility offered by the Hartblei Super-Rotator is

worth paying the extra for, if one can afford it (and if one

can find the lens, as – in 2016 – it appears no longer to be

in production).

Additional advantage of tilt

lenses

As a consequence of using the tilt facility, it is in many

situations not necessary to stop down to tiny apertures in

order to get adequate depth of field (the area within which

the different parts of the image are rendered sharply in

focus). This in turn means that faster shutter speeds can be

used – using a slow film that requires an exposure of 1 second at

f/22 is not much good if you're photographing a field of swaying

corn – or even a building with people walking past.

Of course, product photography

mostly involves work close up, and when any lens is focussed on

objects that are very near to the camera, the depth of field is

reduced dramatically. On such occasions, it is frequently

desirable to stop down the lens aperture somewhat or even

substantially, in order to increase the depth of field.

Experience will reveal the best apertures for different types of

tilt photography.

The Super-Rotator

tilted in use

For the non-shifted performance of the 45mm Mir 26 lens, I would

refer you to the Wide-Angle lens

tests section. Of course, even apart from the shift and tilt

capabilities, there are some major differences.

- Firstly, at least with the Hartblei lenses, a superior

multi-coating is applied.

- Secondly, mount design is far superior to that of many

Arsenal lenses, and the Hartblei 45mm has so far proved more

reliable and sturdy than the Mir 38 65mm Arsenal lens.

As reported on the page on shift lenses,

the expected barrel distortion did not prove obvious with this

lens in most real-life situations.

For a report on results obtained with this lens, click here.

| Mount

incompatibilities

When trying to mount the 45mm Hartblei Super-Rotator

and the 65mm Hartblei shift lenses on my 35mm SLR via

the standard East German Pentacon/Praktica adapter, I

discovered that it was impossible to lock the adapter

onto the lens, as the locking ring wouldn’t

rotate. (Come to think of it, rotating the locking

ring on the Exakta 66 had been difficult!) This

was because the three lugs against which the locking

ring mates were fractionally too thick!! Grinding

them down a little resolved the problem.

There were no such problems with the 55mm Arsat shift

lens.

Restrictions

on movements when a shift or tilt lens is used

on an Exakta 66 with the Exakta 66 TTL

metering prism

There are some restrictions on some movements with

shift and tilt lenses when mounted on an Exakta 66 with

the Exakta 66 TTL metering prism in place, as this

extends quite a way forward of the original front plate

of the camera. None of these movement restrictions

occur with any of these shift lenses if the camera is

used with the standard Exakta 66 waist level finder or

the Exakta 66 non-metering prism.

The restrictions are as follows:

Hartblei 45mm

Super-Rotator

It is difficult to rotate the tilt control (but

there is no problem to change the degree of tilt) once

the lens is on the Exakta 66 if a metering prism is on

the camera, as the front of the prism fouls the tilt

lever. However, there are no restrictions on

shifting in any direction when the Super-Rotator is

mounted on the Exakta 66 with a metering prism, as the

shift mechanism is further forward with this lens than

with the other shift lenses. Also, if required,

the tilt ring can be rotated prior to mounting the lens

on the camera.

Arsat 55mm Shift lens

It is not possible to shift the 55mm Arsat lens very

far up when it is mounted on an Exakta 66 with the

metering prism, as the front of the prism limits

movement. However, as the default shift direction

is sideways (to the left as viewed from above), and as

the format is square, it is not a problem to rotate the

camera through 90 degrees, as we are accustomed to doing

with 35mm and other rectangular-format cameras, in order

to take the photograph.

Hartblei 65mm Shift lens

The maximum upwards shift is 4mm when the metering

prism is on the camera. Shift sideways or down is

unrestricted. Further, it is difficult to mount

this lens on the Exakta 66 with the metering prism

because a ring on the lens presses against the bottom of

the metering prism.

These problems are in fact caused by the

modification of the original Pentacon Six

specification by the designers of the Exakta 66.

It is for the same reason that it is not possible to

mount the Carl Zeiss Jena 1000mm mirror lens on the

Exakta 66 with metering prism.

|

For more information on Hartblei Shift and Shift/Tilt lenses, see

here.

To go back to the section on Other Accessories, click here.

To go on to the next section, click below.

Next section (Test of the Super-Rotator

Tilt-Shift lens)

To go back to the beginning of the Lens Data section, click below

and then choose the range of lenses that you want to read about.

Back to beginning of the Lens Data section

To go back to the beginning of the lens tests, click below and

then choose the focal length that you want to read about.

Back to beginning of lens tests

Home

© TRA December 2005 Latest revision: October 2019